Chapter 9 Fluid Mechanics

The branch of physics which deals with the behavior of fluids is known as fluid mechanics. Fluid is a material that can flow. Gasses and liquids are fluids. Like mechanics it has also three parts, viz, fluid statics, fluid kinematics, and fluid dynamics. Hence in this chapter we are going to study the nature of fluid at rest and in motion very briefly for introductory level. It is easier to deal with fluid’s volume, density, and pressure in fluid measurement rather than its mass and weight. For example, we do transaction of any fluids in their volume (liter) not in their mass (kg). Hence we are introducing some of its general properties.

- Mass Density (or Density): It is defined as a mass per unit volume of the fluid and denoted with a Greek letter, \(\rho.\)\begin{equation*} \rho = \frac{m}{V}, \end{equation*}The density of water at \(4^{o}C\) is \(\rho_{o} = 1 g/cm^{3} = 1000 kg/m^{3} = 1.95 slugs/ft^{3} \text{.}\) The unit of density is \(kg/m^{3}\) in SI system, \(g/cm^{3}\) or \(g/ml\) in cgs system, and \(slug/ft^{3}\) in fps system.

- Weight Density (or Specific Weight): It is defined as a weight of unit volume of the fluid and denoted with a greek letter, \(\rho_{g}\text{.}\) Its unit is \(N/m^{3}\) in SI system, \(dyne/cm^{3}\) in cgs system, and \(lb/ft^{3}\) in fps system.\begin{equation*} \rho_{g} = \frac{w}{V} = \frac{mg}{V}, \end{equation*}\(\rho_{og} = 9800 N/m^{3} = 980 dyne/cm^{3} = 62.4 lb/ft^{3} \) for water at \(4^{o}C\text{.}\)

- Specific Gravity (SG): It is the ratio of density of a fluid to the density of water at \(4^{o}C\text{.}\) It is therefore a dimensionless quantity.\begin{equation*} SG = \frac{\rho_{f}}{\rho_{o}} \end{equation*}Hence, SG of a fluid has the same numerical value as its density in any systems of unit. Since density of water at \(4^{o}C\) is \(1 \,g/ml \) or \(1000 \,kg/m^{3}\) water is normally used as a reference material when calculating the specific gravity for any other materials atleast in CGS and SI system of units. For example, specific gravity of iron is 7.85 because the density of iron is \(7850 \,kg/m^{3}\) and density of water at \(4^{o}C\) is \(1000 kg/m^{3}\text{.}\)Hence\begin{equation*} SG(iron) = \frac{7850 [kg/m^{3}]}{1000 [kg/m^{3}] } = 7.85. \end{equation*}

-

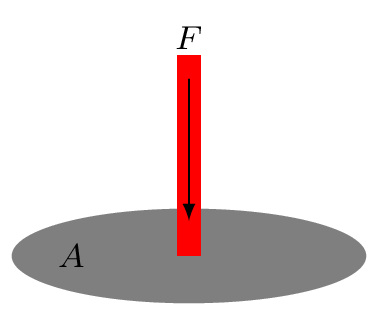

It is defined as a force per unit area of the surface. Here force must be acting perpendicularly on the surface area Figure 9.0.1.(a). Pressure defines how hard the fluid is pushing something in or out. It is a scalar quantity.

1

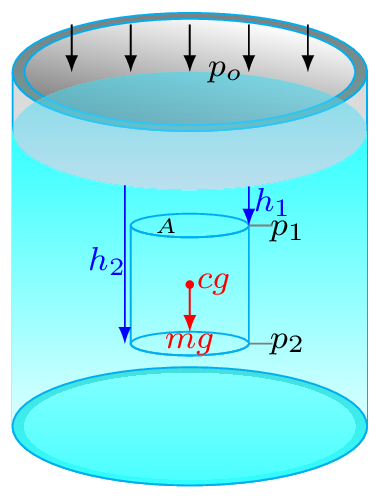

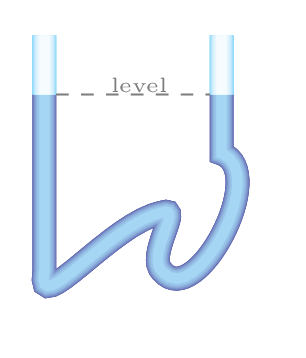

Even though force and area are vector quantities, pressure is not a vector, one reason is that the division of vectors with another vectors is undefined in mathematics, the other reason is that when a pressure is being applied in the liquid, it transmitted equally on every section of its enclosed surface and does not matter what the orientations of these surfaces are. In upper level physics we do study about stress tensor where we define pressure as a tensor rather than a scalar but for now we take pressure as a scalar quantity.It does not have any preferred direction.\begin{equation*} p = \frac{F}{A}, \end{equation*}\begin{equation*} p_{o} = 1 \,atm = 1.013\times 10^{5} \,Pa = 1.013 \,bar = 14.7 \,lb/in^{2}=14.7 \,psi. \end{equation*}Here \(p_{o}\) is an atmospheric pressure. The unit of pressure is Pascal (Pa) in SI system.\begin{equation*} 1 \,Pa=1 \,N/m^{2}, \end{equation*}\begin{equation*} 1 \,bar = 0.1 \,MPa, \end{equation*}\begin{equation*} 1 \,torr = 1 \,mm Hg = \frac{1}{0.76} \,atm. \end{equation*}1 atm = 760 mm of Hg (mercury) at STP (standard temperature and pressure i.e., T=273.15 K and p = 1 atm). Pressure is also measured in psi (pound of force per square inch).In fluid mechanics, three kinds of pressure have been used they are Absolute Pressure: it is a pressure measured relative to a perfect vacuum in pressure scale. Atmospheric Pressure: it is a pressure due to blanket of air (atmosphere) on the surface of earth. Gauge Pressure: it is a pressure measured relative to the local atmospheric pressure. Gauge pressure is thus zero when the pressure is the same as atmospheric pressure.Consider an imaginary elementary cylinder of water inside the water tank as shown in Figure 9.0.1.(b). Where \(cg, \,m,\,A \) are center of gravity, mass, area of cross-section, and \(h_{1}, \, h_{2}\) are depth of the top and bottom portion of the elementary water cylinder, respectively. If water cylinder is in hydrostatic equilibrium (i.e., at rest) then, total force acting on the cylinder must be zero (i.e., \(\sum F_{y} =0,\)) or downward force acting on the cylinder must be equal to upward force at the bottom of the cylinder. Hence\begin{equation*} F_{top} + mg = F_{bottom} \end{equation*}Otherwise this cylinder starts falling down. (The mechanism of upward force acting on the bottom surface of the cylinder will be discussed in Subsection 9.1.2.)\begin{equation*} \text{or,} \quad p_{1}A + mg = p_{2}A \end{equation*}where \(p_{1}\) and \(p_{2}\) are pressures at top and bottom sections of the water cylinder. Now\begin{equation*} p_{1}A + V\rho g=p_{2}A \end{equation*}\begin{equation*} \text{or,} \quad p_{1}A + A(h_{2}-h_{1})\rho g=p_{2}A \end{equation*}\begin{equation*} \text{or,} \quad p_{1} + (h_{2}-h_{1})\rho g=p_{2} \end{equation*}If the top portion of this elementary cylinder is considered at the very top surface of water level so that \(h_{1}=0,\) then \(p_{1} \) is equal to \(p_{o}.\)\begin{equation*} \therefore \quad p_{2} = p_{o}+h_{2}\rho g \end{equation*}where \(p_{2}=p_{abs}\) is called an absolute pressure, \(p_{o}\) is an atmospheric pressure, and \(p_{g} = h_{2}\rho g\) is called a gauge pressure.\begin{equation} \therefore \quad p_{abs} = p_{o}+ h\rho g \tag{9.0.1} \end{equation}Pressure at a depth can be given by \(p_{g} = h\rho g.\) Where \(h_{2} = h\) is depth of water column in the cylinder. Since the pressure can be determined by \(h\rho g\text{,}\) liquid seeks its own level. To keep the pressure same, liquid attains the same height. If a liquid is placed in a container of any shape, it will always find its own level as can be seen in Figure 9.0.1.(c). Atmospheric pressure is also therefore decreases with altitude as thickness of blanket of air above the surface of the earth decreases.